Exactly 50 years ago, on Christmas Eve 1974, Cyclone Tracy struck Darwin and left a trail of devastation. It remains one of the most destructive natural events in Australia’s history.

Wind speeds reached more than 200 kilometres per hour. The cyclone claimed 71 lives and injured nearly 650, and left 70% of the city’s buildings flattened.

If you are about 60 or older, chances are you remember that day, even if the cyclone did not directly affect you.

The 50th anniversary of this disaster offers a crucial opportunity to reflect on how Cyclone Tracy not only reshaped Darwin but marked a turning point in Australia’s approach to disaster resilience.

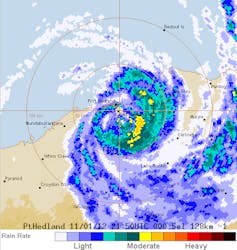

Cyclone Tracy marked a turning point in Australia’s approach to disaster resilience. AP The nightmare before ChristmasCyclone Tracy was initially a relatively small, slow-moving system. But after meandering around the Arafura Sea for three days, it rounded Bathurst Island and headed towards Darwin, getting more ferocious as it approached the coast.

Some Darwin residents later reported not knowing a cyclone was approaching. They included Keith and Christine Pattinson, whose daughter Courtney Zagel later recounted their story:

They told me […] the rain started coming sideways through the louvered windows. The power went out, and everything turned black.

Keith stood against the doors to try and keep them shut, then suddenly there was a huge explosion. The roof of the house flew off and the walls fell in. Christine was thrown back into a glass cabinet. Keith was trapped beneath one of the fallen walls.

The couple spent the night in the neighbour’s house. Christine was later evacuated for urgent medical treatment.

Resident Andrea Mikfelder would later write of the cyclone’s aftermath:

our house […] was still standing. It was a brick home, but the roof was gone. The neighbour’s house looked like a dollhouse, split in half, while the next house was completely flattened.

Cyclone Tracy destroyed 10,000 homes. APThe Bureau of Meteorology would later estimate peak wind gusts of between 217 and 240 kilometres an hour. A report published in 2010, employing more advanced techniques, suggested even higher speeds.

Tracy left about 10,000 houses destroyed and 40,000 people homeless from a city population of 47,000. The damage bill at the time totalled A$800 million.

More than 30,000 residents were evacuated, about 60% of whom never returned. The airlift operation remains the largest in Australia’s history.

Darwin residents being evacuated on a US Air Force plane after Cyclone Tracy. About 60% of residents airlifted out of Darwin never returned. AP What has changed since?In the 50 years since the tragedy, authorities have become much better able to forecast tropical cyclones. They can now warn of a cyclone’s projected path, and the likelihood of it reaching land, several days in advance.

Cyclone Tracy reshaped Australia approach to disaster response and preparedness. The Natural Disasters Organisation – today known as Emergency Management Australia – had been established a few months before the cyclone, to coordinate national-level disaster relief efforts.

But its role and authority were still evolving. Tracy served as a “reality check” for the young organisation.

Cyclone Tracy revealed weaknesses in disaster response at all levels of government. The scale of the damage quickly outstripped local and state resources. The federal government was forced to step in to oversee mass evacuations of over 30,000 people and lead recovery efforts.

However, the Commonwealth lacked clear powers to intervene in national emergencies at the time, complicating its response effort. Its powers have since increased.

Cyclone Tracy also gave impetus to disaster management legislation, such as Queensland’s State Counter-Disaster Organisation Act, established in 1975. Such reforms set the stage for the more structured and integrated approach to disaster response now in place across Australia.

Darwin’s devastation prompted more stringent building codes across Australia.

Even though Darwin is naturally prone to cyclonic winds, few structures had been built to withstand them.

Afterwards, regulations requiring all reconstruction to adhere to updated cyclone-resistant building standards were introduced. It meant, for example, screws rather than nails must be used to hold down corrugated iron roofing, and buildings must be clad to withstand airborne debris.

Thanks to different building rules, Cyclone Marcus caused relatively little damage in Darwin in 2018. Glenn CampbellSimilar regulations were implemented for new construction in other cyclone-prone areas of Australia.

Today, Darwin is a far more resilient city. In 2018 it was hit by Cyclone Marcus, the most powerful storm since Tracy with wind gusts of 130 kilometres per hour. No lives were lost, and relatively few structures were damaged.

Getting to grips with the mental toll

Cyclone Tracy left deep mental scars on survivors.

A study of residents who were evacuated to Sydney after Tracy revealed 58% displayed signs of psychological disturbance in the days following the cyclone. Women and older individuals were particularly affected.

Decades on, survivors described ongoing anxiety and depression, often triggered by the sounds of wind and rain.

Today, the psychological impact of natural disasters – on survivors, volunteers and first responders – is much better understood.

Initiatives such as the National Disaster Mental Health and Wellbeing Framework reflect this progress. It recognises that mental health needs after extreme events are complex, and support is needed at the individual and community level.

Volunteers are keyCyclone Tracy also showed how community efforts and volunteers are essential in disaster recovery.

In the cyclone’s aftermath, local emergency services were overwhelmed. Volunteers quickly became the backbone of the relief effort, setting a precedent for future disaster responses.

Today, volunteers – alongside established relief organisations – still provide food, shelter, medical care and other crucial aid after disasters. As extreme weather becomes more frequent and severe under climate change, the need for community mobilisation will only grow.

The recent Senate inquiry into Australia’s Disaster Resilience recognises the ongoing need to strengthen volunteer participation and management in disaster scenarios.

Volunteers help clean out a home damaged by Cyclone Jasper in 2023. NUNO AVENDANO A more resilient AustraliaUnder climate change, tropical cyclones conditions may occur less frequently. This means Australia is expected to experience fewer tropical cyclones in future.

But a greater proportion of those that do hit are expected to be high-intensity, with stronger winds and rain.

The tragedy of Cyclone Tracy means Australia’s disaster preparedness is more advanced than it might have been. However, building a disaster-resilient nation requires continuous efforts to strengthen infrastructure, refine evacuation plans, and address vulnerabilities in communities.

Achieving this is a responsibility which should be shared between governments and communities alike.