“I do not want to be Russian; I want to have freedom”: An Interview ...

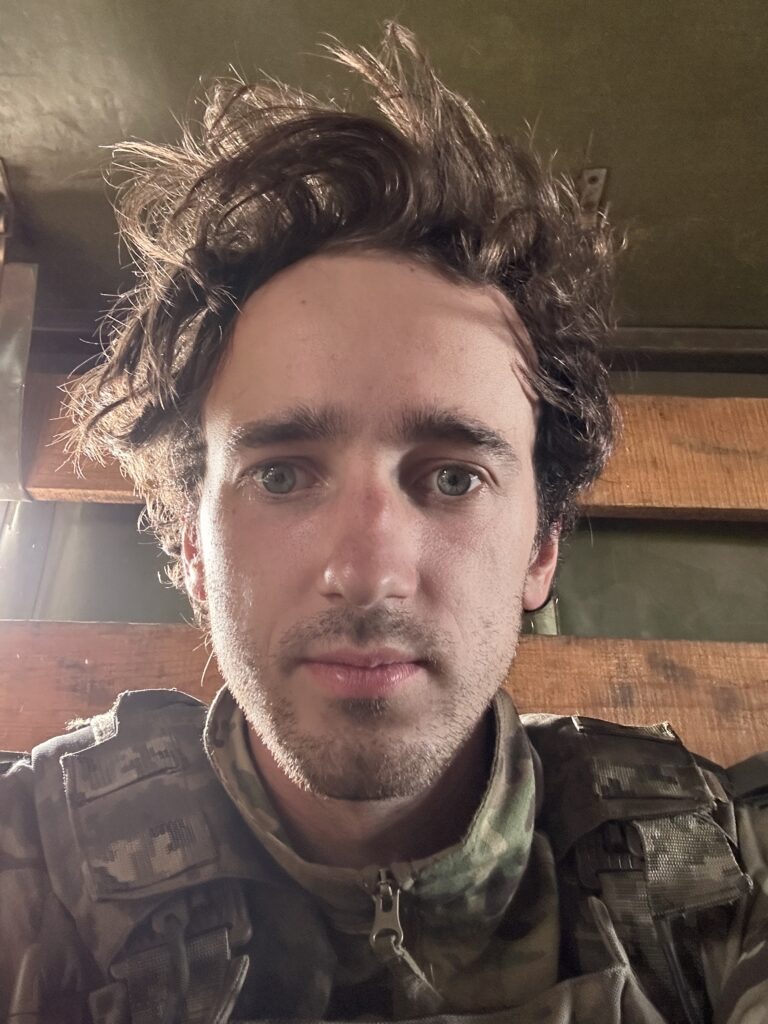

Dmytro Zhluktenko is a 25-year-old former software engineer who has worked for Airbus and Boeing. At the start of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Zhluktenko established the Dzyga’s Paw Fund to help the Ukrainian army, an initiative that quickly grew into a charity raising $100,000 a month and having a profound impact on the battlefield. Zhluktenko married in July and subsequently joined the Ukrainian army, sharing some of his experiences in training camp on social media. In this interview, we talk about his motivation and training.

Yes, my previous role was to raise support for Ukraine. In 2022, when the invasion started, I started writing a lot of posts in English on social media and donating my money to help friends who were fighting on the front line. This impressed a lot of people and they asked me to help them do the same. So it started as a personal thing; then, I was able to set it up in an institutional way, with a charity that has so far raised $3 million worth of technological equipment for the frontline—money raised in 65 countries, primarily the U.S., Europe, and Japan.

It was very important work, but why did you decide to serve in the army?The truth is that I was not obliged to do so because, thanks to the organisation I created, I was legally exempted from military service. The Ministry of Defence came to the conclusion that my organisation and twenty-one others like it were of vital importance for the defence of Ukraine, so I and some of my employees are not obliged to do military service. But I decided to join the struggle. I settled my affairs and joined the armed forces because I believe it is the only force capable of stopping the Russian ideology that they are trying to impose on Ukraine. I have been living through this since 2014 and I am deeply touched by this whole war, which has left me with many scars: I have lost many friends; I have seen friends maimed; I have seen what happens to cities when they fall under Russian occupation. I know that, just as they have deprived Ukrainians in the occupied territories of their freedom, the same will happen to us. To make a long story short, I do not want to be Russian. I want to have freedom, I want to have self-determination—to be able to believe and say what I want, and not to be drafted into an invading force marching on Warsaw or anywhere else. I want to be able to live a normal and free life, to defend my freedom and the freedom of those who cannot defend themselves.

You recently got married. I understand your wife supports you in this decision.Absolutely. We talked about this decision for a long time. Still, it has not been easy, but I am the one who has to fight for her. Of course, it is mentally difficult for her to see that I am risking my life and that I am far away; I guess that is the hard fate of soldiers’ wives.

Freedom is not free. When the war started in 2014, I was a teenager and I couldn’t understand everything that was going on. I read books, I started to understand what it meant to take away people’s freedom, and I saw how they turned the occupied territories into a dunghill, so I understood that I didn’t want the Russian occupation. When you see places like Bakhmut, which has been totally destroyed, you understand that it will take many years to rebuild everything. But the worst thing is not the damage to infrastructure or buildings: I have met people from eastern Ukraine whose lives have been completely taken away from them—people who have lost their freedom.

You posted on social media that you have completed your basic military training. What was that like?It was quick—just over a month—and I would have liked it to be longer, but it was good training. In total, I’ll have had three months of training before I’m sent to the front. The Russians have cheap resources and cheap people—even convicts—and they don’t care about their lives or their training. In Ukraine, we don’t have that luxury. We have to care about every life: first, because the value of human life is one of our most precious values; and second, because from a practical and military point of view, we don’t have as many people as Russia. That is why we invest so much in the training of our soldiers. In the Ukrainian army, it is now compulsory for all military personnel, even those doing bureaucratic work 1,000 kilometres from the front line, to receive basic infantry training, learning how to dig trenches, how to fire a rifle, and so on. The plan is to double this training from one to two months by the winter.

Your instructors were veterans. Some of them had even been prisoners of war. I think you were trained for this situation?Yes, one of our instructors was a marine captured in Azovstal who had spent ten months in captivity; and yes, we were trained for it. Both I and my comrades-in-arms have seen many pictures of prisoners of war, and we have been taught tactics in case we are captured—for example, how to escape from our captors. We have even talked about the psychology of torturers. I think that strengthening mental resistance is also very necessary.

The images of the exchange of Ukrainian POWs show evidence of torture and starvation in many cases, and there have also been videos of prisoners being executed by the Russians. What goes through your mind when you see these images?We know that the Russians don’t respect any kind of convention, and that treaties are a fiction for them. You may think it’s unfair that we respect the prisoners and they don’t; but, at the same time, it’s a question of dignity. At no time in my life have I ever wanted to kill or shoot another human being, but now I’m in the army and that’s what I have to do. But I would never want to torture another human being, because that would take away part of my soul and my dignity. Honestly, I have no respect or sympathy for the invaders, but I know that every Russian prisoner of war is probably going to be exchanged for a Ukrainian prisoner of war. My trainer told me a lot about what he experienced in captivity, and it’s terrifying, so our priority is to free all our POWs from those unbearable conditions.

The fact is that the Ukrainian army has behaved very differently from the Russian army, as we saw in the Kursk operation and in the treatment of Russian civilians. Is there an insistence in training to behave as part of a ‘civilised’ army?Absolutely. There is discipline, there are rules and rational decisions that we have to follow. I think the general feeling among soldiers in the Ukrainian army is that it is more advantageous to take prisoners than to kill them. And the same applies to civilians: what is the point of killing, raping, or pillaging the civilian population, as the Russians did when they tried to storm Kyiv in 2022? It makes no sense at all. The Ukrainian army is not doing any of that in the Kursk region, because we are behaving like a civilised army, and a civilised army does not engage in abusing the innocent. It is another black and white situation. Again, I have no sympathy for Russian civilians, but I will not lose my dignity.

Why are you sharing your story and your training on social media?I think my example is proof that the Russian narrative—that Ukrainians don’t want to fight and are forced to enlist—is false. I didn’t have to fight, because I was exempted. But I can’t stand by and watch what the Russians are doing to my people; I don’t want my family to see what’s happening to their towns; I don’t want my friends hiding in shelters because of Russian missiles; I don’t want a stupid war on my doorstep.

And that’s how it works: if we don’t keep the front in Donetsk, then the war will come closer and closer—to Dnipro, to Kharkiv, to Kyiv, to Lviv, and finally to Warsaw. In 2022, we were one step away from disaster, and that is why we must contain the enemy and save the sovereignty of Ukraine. If Ukraine is defeated, many like me will be forcibly conscripted into the Russian army—as has happened to the ‘liberated’ population of Donbass—and forced to go to a new war with Chechen soldiers on their backs so that they cannot retreat. This is not a local conflict, it is something much bigger, something which has, so far, been contained by the Ukrainian defenders.